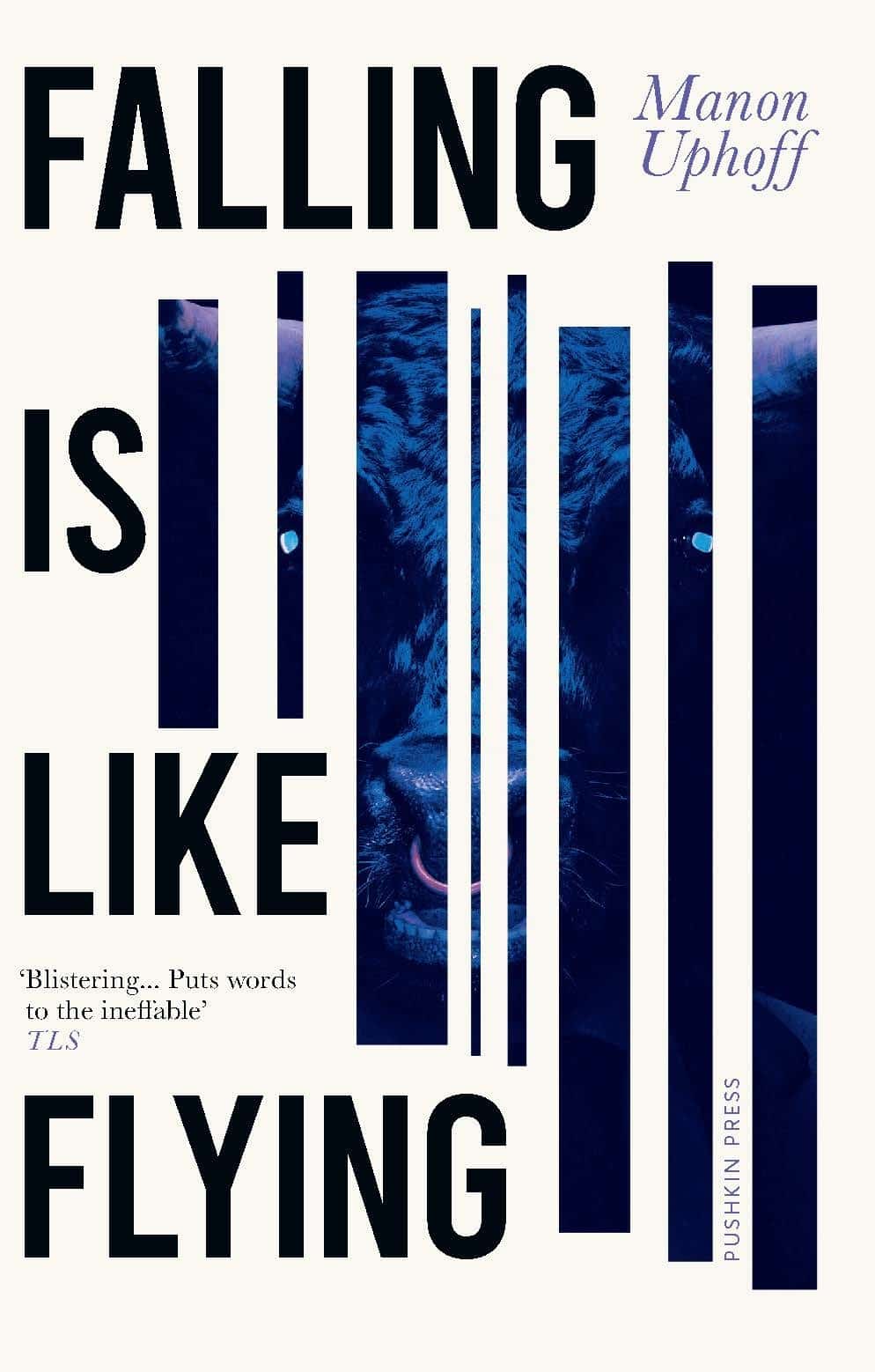

Fury of Extraordinary Proportions: ‘Falling Is Like Flying’ by Manon Uphoff

For over 25 years, Manon Uphoff has written novels and short stories that are populated by complex characters in troubled relationships. Falling Is like Flying is no exception. This novel delves into a painful personal past in search of love and identity.

When her starving sister, sixteen years her senior, falls down the stairs and dies, the writer finds a fury ignited within her like a fuse. The death of Henne Vuur, her stepsister and one-time surrogate mother, forces the author to confront a gruesome and frightening past. Simultaneously acting as prosecutor and archivist, she records this past. Central to the story stands the father Holbein, an amateur artist, statistician, ex-convict, seminarian drop-out – and God of a labyrinthine world.

“He was a troubled, deeply damaged man (which I only now dare to say). He had temper tantrums, sought inappropriate outlets for all his emotions and desires, inflicted pain and suffering upon his (step)daughters.” And so the truth comes out, straight and dry, with an impact that is difficult to comprehend.

Simultaneously acting as prosecutor and archivist, she records the past

The “undersigned” I-narrator appeals to the reader, telling the story from the inside. The perspective of a four, six, eight, twelve-year-old child shifts to that of the adolescent, then the adult, each time shedding new light on the bizarre and sullied past. Uphoff cleverly lards these evolving memories with fragments that go further back. Back to the time before “the Minotaur”, as she calls her father, delving into the history of the complex composite family into which she was born, teasing out alliances that as a small child she only barely, through trial and error, began to understand. Writing from the heart of family life, she captures a multifaceted experience without falling into the trap of social judgment from the outside.

Manon Uphoff

Manon Uphoff© Celine Simons

Sparing no one the grizzly details, Uphoff describes her father’s nocturnal visits as the stuff of fantastical nightmares: “This Escheresque rabbit hole in which (…) our bodies were united with the Minotaur, squeezed together and pulled apart in a starry twinkling of dancing nerve cells (…)” The language rushes and churns, a maelstrom of images, smells, and sensations between waking and sleeping, all in the dark. Memories in distorted mirrors, associations forever perverted, Alice in a wonderland of morbid fascination.

What is it like to grow up in a family where the notion of closeness and security is turned on its head? More than just an indictment of years of abuse, this novel is an investigation into what “home” means, even in the toxic but befuddling context in which Uphoff was raised.

The book opens with “the long winter of our displeasure”, just one of many references to Shakespeare that are subtly woven into the story. The undersigned candidly explains how the rich colour palette of her writing is rapidly fading, how an ever greater silence imposes itself. The suggestive has its value, but it doesn’t last. The author understands that this is a crisis she must go through in order to emerge stronger.

Abuse and childhood trauma – surely the book is an example of therapeutic writing? But no, there is none of that. Uphoff opens Falling Is Like Flying with an apology to the reader: “I didn’t mean to tell this story.” But she tells it anyway – it’s like she has no choice. Many of her stories are about dysfunctional families: in De vanger (2002) and De bastard (2004) she uses the enclosed setting of the home as a bell jar through which to sublimely examine the human condition. De ochtend valt (2012), too, is practically a sociological experiment with a fairytale twist.

Falling Is Like Flying exposes where this tendency originates. The dizzying eruption of images, impressions and experiences provides insight into her childhood in the dysfunctional Holbein family. Father Henri Elias Henrikus Holbein – also called HEHH, an abbreviation that reminds us of the book HhhH (Himmlers hersens heten Heydrich – Himmler’s brains are called Heydrich) by Laurent Binet – rules the family like a mythical god. He exerts control over the minds and bodies of the Holbein women. The threat and oppression of the imposing, feared, and worshipped father figure lies like a haze over the entire story. Yet he is also a loving father who introduces the undersigned to art and literature, who cooks well and feeds her all kinds of goodies, and who makes her feel as though she is special – which leads in turn to new manipulations.

“Ach,” he says. “Are you there, child”, and I feel his loneliness and want to sit with him, I want to help him solve the riddle. And I roll up my wool and bury the thread.”

In this novel, nothing is “processed” or “set aside”, as so often is done in literary confessions of traumatic childhoods

The domestic and the gruesome are inextricably entwined. The everyday fosters a certain safety, but within it, the almost mythically abject manifests. It infects everything with a stain, of which she only later becomes fully aware. Uphoff expresses shame and uncertainty and hesitates until the very last pages to reveal her secret – because how could something like this possibly be received? Remember, for instance, the vitriol towards Griet Op de Beeck when she came out with a similar story – admittedly vague though it was. It can’t be true, the reader doesn’t want it to be. The unwanted story is refused, the world can’t tolerate women’s fury. But what Uphoff does with this fury makes it inescapable. Here, nothing is “processed” or “set aside”, as so often is done in literary confessions of traumatic childhoods. Uphoff transcends the typical roles of perpetrator and victim. Words like “abuse” or “incest” are never explicitly written. Through the richness of form and a book that bursts at the seams with beautiful language, Uphoff/the undersigned exhibits – finally, after all these years – mastery over this overwhelming story.

Here speaks an injured woman who is no longer a victim, but who has reconnected with her basic instincts, cast away her shame, and escaped the curse. By getting this story out, she no longer has to suffer the secret, the years of bending to her family’s wants and needs, and to that of a father who crossed every line with impunity.

Like the fairy tales that the girls grew up with, this story is archetypal in all its tragic particularity. Jungian or not, stories are healing, and literature, film and music are all generously referenced throughout. Stylistic mastery lifts this book and gives it a driving force that will knock you back. The facts are terrible, but even more impressive is the way in which they are handled.

Literally turning raw pain into a zest for life – that takes a great deal of courage

“Amidst this wretched upbringing there is also the comfort and the pleasure of the extraordinary, the ordinary. (…) Upon awakening you hear the blackbird sing. Is it time for revenge, or reconciliation?”

This, it seems, is the essential question. The story works towards the catharsis of a grandguignol. Upon a witches’ sabbath, the wounded sisters solemnize their mayhem. Like the three weird sisters from Macbeth, the undersigned and her sisters Libby and Toddiewoddie take revenge in their own Walpurgisnacht for a life of crushing abuse, violence, beauty and pain. The ritual of expulsion is imperative – the father figure must be ritually destroyed. By revealing their secret and drawing out the ending, the sisters include as much of their own story as possible, with liberatory anger and laughter having a redemptive effect.

At the very end, Uphoff zooms out. She gives the last word to the elementary will to live as manifested planetarily; naturally. The private, even the trauma, is magisterially transcended in an ode to female anger that looks nothing like hysteria. That energy is the engine behind the book and gives the deceased sister back her voice. Fear and lust, longing and neglect, vulnerability and incredible resilience, love and hate, all flow into a captivating reading experience where red-hot language sends sparks flying.

It is a triumph of the wild, inner spirit and of a powerful imagination that Uphoff has survived in this way. Literally turning raw pain into a zest for life – that takes a great deal of courage. With sheer will, she shifts the perspective. Manon Uphoff shows us in this way that falling can also be like flying.

Manon Uphoff, Falling Is Like Flying, translated from Dutch by Sam Garrett, Pushkin Press, London, 2021, 192 pages